Part 7: Brilliant no-holds-barred racing could not sustain

Faced with the apparent success of the South African Manufacturers Challenge and after losing a few competitors and factory teams to that burgeoning free-for-all juggernaut, the Group 1 hierarchy opted to forego its standard production ethos for the series for 1981. The showroom series was however handed a significant reprieve when the Challenge imploded en main due to its freedom of regulations, cost and the huge political fiasco all that brought with it.

Up to then, certain aspects had remained consistent in the two decades since production car racing had first emerged in South Africa. Brands like Alfa Romeo, Renault and Mini, had all been involved at various levels from the outset and all three were very much still in the results. Alfa’s success in particular, had always been down to its standard cars being engineered at another level – those Sprints, Giuliettas and Giulia’s, GTs, and GTVs’ twin-cam engines and five-speed gearboxes were way ahead of their time, which made them unbeatable in production car racing.

Of course the similarly endowed big Jaguars had enjoyed similar advantages in the early years, while the likes of the Mazda rotary and other wieldy lager capacity machinery such as Ford’s Cortina 3.0S also came to the fore over the years, not to mention early homologation specials in the mould of the Fiat 131 Racing. There was nevertheless always a twin-cam Alfa in the championship mix, never mind that Coenrad Spamer and Giovanni Piazza Musso won three of the five SA Group N championships that ran until 1980.

So, after another lean year of Mazda domination up front in 1980 with Tony Viana, Peter Todd and Jannie van Aswegen up front in Class V, Giovanni Piazza-Musso in a new Alfa Romeo Giulietta, Jan Hettema in Toyota SR5, Louis Parsons’ Alfa Veloce in Class X and Keith Burford Avenger showing the way in Y upcountry, while Koos Swanepoel, John Simpson and Terry Thornton in the Mazda Capellas, Pietie Smit in an old Alfa GTV and Serge Damseaux a new Alfetta GT diced Gerald Bessesen’s Cortina in the Cape, Group 1 was all change for 1981.

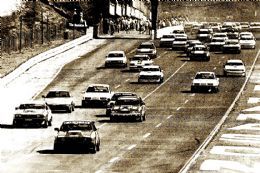

With the demise of the Manufacturers Challenge, Group 1 was once again set to become South Africa’s major saloon car racing attraction. Emerging on top of a paint-swapping car-crunching melee with door handles and wing mirrors flying was still what carmakers cherished most and what the crowds came to see first.

The powers that be had also figured that South Africa’s parlous standing in the world politics created a performance saloon vacuum, to which Group 1’s new homologation era would provide a splendid solution. Not only would such a race series provide a fantastic marketing tool considering the sport’s cult following but building and selling homologation specials for a performance starved public was already a proven brilliant business model. Never mind the kudos of a carmaker coming out on top of its market rivals in a cauldron that delivered test match level of aggro both on and off the racetrack.

So, undaunted by the failure of the unlimited Manufacturers Challenge, Group 1 embarked on a mission to free up its regulations. While competing cars still had to be locally manufactured, out of the window flew the need to race on South African produced road tyres, standard engines and many other aspects that guarded Group 1’s promise of showroom stock racing. In came control slick tyres and engine compression ratios freed up to a pretty high 10.5:1 back in the days of carburettors and the occasional most basic fuel injection.

Limitations on camshaft timing and cylinder head porting were also eased, as were exhausts tailpipes from the manifolds back. Crucially, another major change was that Group 1 homologation numbers were further dropped to require only 200 similar cars to be, to make it easier to build and sold through dealerships as road cars, to qualify them to race on track and make it even more attractive to the carmakers to compete.

All these changes would ultimately prove a double-edged sword – they brought brilliant racing in the short term, but the long-term ramifications would once again prove another brilliantly conceived South African tin top series’ ultimate downfall….

Compared to the recently imploded free-for-all Manufacturer Challenge, Group 1 still offered a ridiculously cheap entry point – preparing a standard-based car was a far simpler and more cost-effective task and the spin-off far exceeded rival marketing and publicity options, never mind the lack of complexity of racing in a less modified series.

Of course, all that also yet again flew in the face of the good old ethos of keeping production car racing cheap for the privateer, but before anyone knew it, more and more carmakers were flocking to the Group 1 racing fold.

Not having a performance saloon car capable of winning in Group 1 racing on its pricelist, Ford was the first to respond to the allure of preparing a car to race. The faithful Cortina V6 was already well proven in 3.0S form from a couple of seasons prior, but it had become outgunned and disappeared off the grid, when the Blue Oval came up with a plan to reinvigorate old faithful and reinstall Sarel van der Merwe and Geoff Mortimer in a pair of uprated Cortina XR6s, while Tony Viana wasted no time in acquiring an Interceptor of his own.

Alfa Romeo meanwhile timed the release of its new 2-litre GTV perfectly – basically the facelifted, more powerful facelift of the outgoing and well proven 1.8-litre Alfetta GT with young Nico Bianco entered in a factory car and Modified refugee Abel d’Oliveira driving a Dawie de Villiers prepared version. Every other man and his dog had meanwhile scrounged a raceworthy Mazda Capella or RX2 to take on the newcomers in top Class U, with Willie Hepburn, Collin Burford, Paolo Cavallieri, Tommy Voget, Ralph Lange and Paul Cox among a sea of them.

All the smaller classes were closely fought too – Alan Esterhuizen and Dick Pickering’s Alfa Romeo Giuliettas, Alfettas Ford Escort RS2000s and George Bezuidenhout at the tiller of a Datsun 280L made up Class V. Giovanni Piazza Musso and Louis Parsons’ Alfa Export Veloces and Eddie Nel’s Golf GTS were in in W, Jan Hettema in a Toyota Corolla GL and Jim Smith’s VW Passat among the Class X lot, while Bob van Noord, Charles Brittz and Anvar Haffejee’s Alfasuds took on Ron Samuel’s Datsun 140Y, Jack Clinton’s Kadett and Keith Burford and Hein Lorentz’ Avengers in Y and Andy Turlouw’s Renault 5 was up against Abdul Wahab-Jaffer and a fleet of 1200 Alfasuds in Class Z.

Group 1 was into its wilder new era in spectacular style as van der Merwe, Mortimer, Bianco and d’Oliveira delivered some incredible races mixing it with Viana and the Mazda gang up front, with close racing throughout the field. But the game was moving on fast and not only was Group 1 now runaway success, but it had tempted the likes of BMW and Mazda into the fold. The existing players were also a step or two ahead too.

It was once again all change for 1983 as a new premier Class T was added to accommodate the thrilling prospects of BMW’s imminent arrival with the new 535i and Alfa Romeo’s response with its much anticipated 2.5-litre GTV 6

While it had found success in Modified Saloon Car racing with its 530i since racing resumed following the Fuel Crisis a few seasons prior, Group 1 was the perfect playground for upstart BMW to showcase its competition-oriented streetcar tech against their rivals, never mind that its all-new 535i was a regular car with a competition heart and so perfect for standard production racing.

Knowing his previous success with the likes of the Fiat 131 in Group 1 racing, BMW engaged Tony Viana to spearhead its new factory effort with Paolo Cavallieri as his wingman and Cliff Coetzee in support in a third privateer entry.

But Alfa Romeo was ready and waiting too – it’s all new GTV 6 was technology-packed in true Alfa tradition. The GTV already packed a transaxle rear gearbox and differential unit and de Dion rear suspension combined, inboard rear disc brakes to reduce unsprung weight, so the chassis was already primed and well proven with all it ever needed to be nimble. Add Alfa’s all-new fuel injected V6 and GTV 6 had the potential to take on the mighty new Beemer, but was it enough?

Alfa however soon figured that Group 1 allowing a 10.5:1 compression ratio, wilder camshafts and heavier valve springs made all the difference. All that, combined with the usual, meticulous state of the black art of Group 1 tuning the likes of precisely statically and dynamically balancing the engine and drivetrain reciprocating parts, meticulously measuring, blueprinting, matching and flow optimising cylinder heads, inlet and exhaust manifolds and studiously re-assembling the lot, made the GTV 6 a winner out of the box.

Any other Group 1 racer worth their salt of course did much the same – while modifications were limited and did make a difference to a race car’s pace, just as significant performance gains were available via the blueprinting process. That in essence means that every component in a competing car’s engine and drivetrain is meticulously honed and fettled to match its actual design blueprint.

See, most car components have a variance to their design spec, which usually contributes to performance losses, so by making sure that an engine is perfectly to its intended design specification, can most often yield more performance than actually modifying the allowed components could achieve. And that is the real ethos of ‘standard’ production car racing…

So not only was its new weapon capable of pulling a 6 700rpm, or an almost unheard of 240km/h down the old Kyalami main straight, but Alfa’s GTV 6 was after all quite up to the litre-bigger and more powerful straight-six but also significantly heavier and bulkier and likewise fuel injected BMW.

Not to be outdone, Ford meanwhile took a leaf from Basil Green’s book and slapped a ‘Six Pack’ onto the vee of that old Essex lump nestling in the engine bay of the good old Cortina XR6. Comprising a trio of twin downdraught Weber carburettors atop a custom inlet manifold, Bernie Marriner and his men up-rated the Cortina’s suspension and brakes in such a manner that a so-equipped premier class Group 1 racer would be right on the button against the those newfangled BMWs and Alfas.

The marketing men applied a set of Ford racing stripes and stuck an individualised, numbered badge plate onto each so-blessed Cortina’s D-pillars and Interceptor was an instant classic as the 200 street cars were snapped up in a flash.

So, the 1982 title fight delivered a spectacular Alfa versus Ford versus BMW battle up front with a similar fleet of 2-litre Alfa GTVs and Mazdas fighting in Class V and the rest of the classes more or less as they were. But Mazda was not taking losing its overall winning advantage lying down and it too had a trick up its sleeve…

The Group 1 game moved another step on when Willie Hepburn and Ben Morgenrood turned up to take on the might of Alfa Romeo, BMW and Ford armed with a pair of brand new Class T Mazda RX7s. SAMCOR had arranged special dispensation to race the imported RX7s, complete with the latest spec rotary engine technology and the advantage of drawing from the vast local and international rotary knowledge bank on how to make the little engines spin ever more efficiently for race use.

It never took the terrible twins long at all to get the knack of things either, as Morgenrood put it on pole for Killarney’s False Bay 100 races with 1minute 27.2 second lap, over a second quicker than the BMWs and Alfas and close to two seconds faster than the Interceptors, which prompted Ford to reconsider its options. As a matter of interest Tony Viana’s Full-house Modified Racing 535i only turned a 1m 24sec lap on raceday – not all that much faster than his ‘standard production’ 535i!

The racing was fraught, with a 17-year old lad by the name of George Fouche joining the fray alongside d’Oliveira and Bianco brothers Nico and Maurizio, BMW refugee Paolo and his brother George Cavallieri in the Alfas and Viana backed by Fanie Els in the BMWs. Ford’s venerable overhead-valve Essex V6 meanwhile had nothing more to give at the level that Group 1 had evolved to and with van der Merwe and Mortimer off to rally for Audi, the Motor Company had to rethink its racing options.

Behind the frontrunners in Class T, the likes of Tony Troskie and Bob van Noord’s faithful Mazda Capellas took Maurizio Bianco’s Alfa GTV 2000 on in Class, U, Pickering and Esterhuizen’s Alfa Giuliettas had Paul Cox’s significant Datsun 280 L to deal with in Class V, Jan Hettema’s Toyota Corolla SR was up against Peter Lanz in an Ford Escort XR3 Perana in Class X and Charles Brittz and Eric Sanders’ Datsun Pulsars battled Graham Cooper’s Renault 5 in Class Y.

The Mazda RX7s were not the only revelation, as another shake-up unfolded further down the pack as the Group 1 evolved. Up until then, Alfa Romeo’s evergreen all-aluminium twin-cam engine had been around for three decades already in some form or another since the first Giulietta 1275 in 1954 and was still winning races in Group 1’s smaller classes with twin side-draught Webers on 1.8 and 2-litre variants of that classic engine.

But that would also soon change when Volkswagen South Africa finally got round to unleashing its long-awaited giant-killing Golf GTi in South Africa. It inserted none other than its quattro rally drivers Sarel van der Merwe and his ever faithful wingman Geoff Mortimer in a pair of boxy GTis to take care of Group N’s traditional Alfa twin cam stomping ground Class V to devastating as its groundbreaking new fuel injected single overhead cam hatchbacks proved an instant success.

Those venerable contemporary Class V Guiliettas were however not the only Group N cars under threat, with Ford’s Interceptors already out of the picture and the Alfa GTV 6 feeling the evolved BMW 535i and Mazda RX7 pinch too.

Alfa Romeo was desperate to respond to the Mazda RX7s and ever-improving BMW 535is, when company public relations officer and a leading racing light alongside company boss Vito Bianco, Roger McCleery noticed an odd-looking V6 engine lying in the corner of Alfa Romeo’s Italian factory Autodelta race team workshop in Milan while leading a press visit to the facility. Investigating further, Roger discovered that the one-off rally engine was indeed a three-litre unit with a trio of Ford-like Six Pack like Weber IDAs in place of the regular 2.5-litre V6’s fuel injection.

McCleery rushed from the airport to Alfa’s Louis Botha Avenue HQ to report his discovery to Bianco as soon as he could after that Alitalia 747 touched down at Jan Smuts and before anyone knew it, Alfa Romeo South Africa had ordered 200 GTV 6 assembly packs from Italy. Once here, their 2.5-litre V6s were converted to 3-litres, the fuel injection ditched in favour of those IDAs before the new engines were slotted into the awaiting chassis at its Brits assembly line, while a neat NACA duct was applied to the bonnet, among other special bits.

So confident was Alfa Romeo of its new Group 1 monster’s potential that it sponsored the Sports Car Club’s late-September 1983 Kyalami raceday. It was a risk well taken as the new GTV6 3-litres blocked out the front two rows of the grid in a top four whitewash, before Abel d’Oliveira and George Fouche romped home to win the Lodge 2 Hour Group 1 endurance race from the Morgenrood RX7 and Nico Bianco and Arnold Chatz in another GTV6on the powerful new 3 litre’s debut.

BMW and Mazda were taken aback by the GTV6’s dominant debut as Viana, Morgenrood and Hepburn scratched their heads, trying to figure a response, while there was already something going on down PE way, if reports of some rather rough sounding Sierras testing at the Ford proving ground and Aldo Scribante racetrack were anything to go by.

Group 1’s lower classes had meanwhile become the playground of the dominant van der Merwe, Mortimer, Peter Lanz and Clive Cooke’s Golf GTis challenged by Alan Esterhuizen’s Alfa Romeo Giulietta Group One and Tommy Voget, Michael Sapiro and Danny Moyle still leading the good old sea of Mazda Capella rotaries and the odd Toyota Corolla Liftback TRD.

Behind them was another homologation special spat between Louis Parsons’ Alfa Sprint Veloce, Phil Webb and Peter Lindenberg’s Ford Escort XR3 Peranas and Tienie Oosthuizen’s Toyota Corolla SR5. At the back came the usual splendid spat between the likes of Koos Roos and Mike Wentzel in Nissan Pulsars, Graham Cooper and Andy Turlouw’s Renault 5s, Chris Clarke and Abdul Wahab-Jaffer’s Alfa Exports and even Hein Lorentz in a Honda Ballade.

Down in the Cape meanwhile, although it occasionally ran with the regional Modified class, Group 1 racing remained ever popular with Koos Swanepoel at the helm of a Mazda RX7 against the likes of Leon de Kock and Pietie Smit in a pair of Alfa GTV 6s and Wally Dolinschek’s Cortina Interceptor, while Hannes Oosthuizen’s Golf GTi, Pieter de Waal and James Andrews’ Toyota TRD and Tony Norman’s Renault 5 were among the men doing battle in the classes.

That rumbling from Port Elizabeth soon exploded into a roar when Ford’s long awaited response arrived in the form of Cape Town race and rally hero Serge Damseaux aboard the all-new 5-litre V8-powered Sierra XR8, of which the plant was churning the prerequisite number of road-going homologation specials too. Mick Jones and his men however underestimated the force of Alfa’s attack and also miscued on tyre sizes, as the 3-litre GTV 6s locked out the top three places on the grid and made off up front.

Undaunted, the Ford team went back and did its homework and few months later, Damseaux blasted the V8 Sierra onto pole at Kyalami and went on to lead most of the race, only to retire with mechanical problems in the face of the mighty Alfa Romeo wave. The XR8 finally overcame the dominant GTV 6 3.0s at the twisty little Lichtenburg track, when Damseaux passed George Fouche for the lead late in the race and held him off to score a sensational 0.4 second win, late in ’84

You may be wondering what happened to BMW and Mazda at this point? Well Mazda had no answer to the arms race that Group N had become and went off to concentrate on Modified Saloon Car racing, but BMW was quietly working on its secret project, both at its Midrand race HQ and in the Rosslyn plant and its response was spectacular.

Of all the mismatches in motorsport history, the 745i must rank among the most spectacular – BMW South Africa not only pinched the fire breathing blueprinted 3.5-litre 24-valve twin-cam straight six out of its M1 supercar, but it slotted it into the most unlikely car on its range – a 7 series limousine to make a race car out if it! In order to qualify to race it, BMW SA also had to build necessary number road cars too, all in search of winning on Saturday to sell on Monday. In so doing, BMW South Africa has also unofficially built the first real BMW M sedan too.

True to form, the big new Beemer was another mighty beast built to win on track and Tony Viana celebrated the team’s return by planting it on pole position for its Kyalami debut. Alas, the dreaded lurgy that so often befalls a new race car struck three laps in, when a clutch pin broke, the race leading 745i over-revved and swallowed a number of choice Bavarian engine bits to leave Bianco’s GTV 6 3.0 to break the lap record en route to victory through a Fords versus Alfa battle of huge proportion, but only after Damseaux had thoroughly stuffed his rasping XR8 into the Sunset wall.

The racing went on to become a no-holds-barred BMW-Ford-Alfa Romeo war both on and off the track. But that old South African saloon car racing bugbear of winning at any cost was once again raising its ugly head. Never mind that Group 1 was originally conceived as a showroom stock production car class to to attract privateers to affordably compete at top level ten years before, but it had by then had evolved into another megabuck South African factory team fracas racing specially developed super saloons at the highest level.

To complicate matters even further, the fledgling Group N series was once again catering for the very values that Group 1 had forgotten and was rapidly gaining momentum in two new championships both upcountry and in the Cape following a debut 6 hour at Killarney.

Group 1 had nonetheless, evolved into something of an adrenaline overload. As much as it was war on track, it was just as crazy in the grandstands, where a cult following rooted for their heroes to the to the point of fisticuffs as the circus it travelled around the country. Back on track Viana hit back with a vengeance, breaking the lap record on his way to victory at the next Kyalami race, but it all came apart at the seams at the penultimate round of the 1985 season at Kyalami.

In one of SA racing’s most famous stories, race officials impounded the top six finishers immediately following yet another desperately close three-way Group 1 battle in which Bianco had overcome Viana and Damseaux to steal a famous victory and clinch the championship in his black Alfa Romeo GTV 6 3.0. Race scruitineers sealed the bonnets of all the top six cars, all of which were to be trailered to Arnold Chatz’ Craighall Park workshop in a convoy, where they were to be to be stripped alongside the class winners and all the Group N winners of the day, to determine their compliance with the prescribed regulations.

Bianco’s team boss Dawie de Villiers however arranged that Nico's car be allowed a detour to a crucial advertising photoshoot out in Pretoria en route. The black Alfa duly joined the strip two hours late, by when champagne sprayed in the shoot had become caked in a dusty crust over the and the rest of the front of the car bonnet on the way in. Most astoundingly however, when the car’s cylinder heads were stripped off, their combustion chambers and port tracts showed no sign of use – there was not a trace of exhaust carbon anywhere!

The perplexed scruitineers re-sealed the Alfa’s engine bay and attempted to access the without removing the seals in an effort to prove the engine had been tampered with between Kyalami and the strip. but they failed to properly unclip the bonnet stay runners and were thus unable to prove foul play. The case indeed went to race court on the basis of it being impossible that there could not be carbon on the engine components after a hard race weekend.

The astute lawyer that Nico Bianco was in his day job however toyed with the AA Motorsport jury and Alfa Romeo won the case, the race and the championship. Whatever happened that afternoon after the bonnet was sealed and before Bianco’s car was stripped, will probably forever remain a secret!

To add insult to injury, Damseaux’ XR8 was found to have been illegally modified and Ford appealed, admitting that incorrect cylinder heads were somehow fitted in error! A further fiasco unfolded at the following race just a few weeks later when Bianco’s team refused to allow his winning car to be stripped at all, while the Fords were once again were found to be illegal.

Group 1 had coincidentally become a South African championship once again for 1985 following a few years without national status, with Tienie Oosthuizen’s X class Toyota TRD taking the overall championship while Tony Viana took Class T and Nico Bianco Class U. Charles Britz took Class V in his Nissan Skyline, Peter Lanz’ Ford XR3 Perana won Class W and Mike Wentzel Class Y in his Nissan Pulsar.

But with Alfa Romeo and Renault among the many carmakers exiting South Africa under the cloud of sanctions, Ford fed up and BMW left with nobody to race, Group 1 collapsed as Ford and BMW went off to join Mazda in Modified Saloon Cars. In desperation, the series morphed into the similar new international Group A, but its real problem was that Stannic Group N had picked up the standard production baton that Group 1 had dropped and had already proven fiercely popular.

The beauty of tightly controlled Group N racing was that it severely limited modification of its cars, which were basically blueprinted stock standard road cars running on South African produced road tyres. That meant no matter how good the factory was, a clever and competent privateer could still compete in what was a relatively inexpensive and highly competitive form of standard production car racing.

Group N also once again afforded the man in the street the opportunity to race his road car on Saturday and drive it to work on Monday and still have a chance of being competitive, while race fans could readily identify cars like they drove every day, racing flat out and hopefully winning on track.

So once again, just as it had been when Group 2 took over from Group 5 fifteen years before, and again when Group 1 started from scratch out of the Fuel Crisis in ’74, the bulk of the existing Group 1 competitors converted their cars to Group N specification, leaving the few who remained to carry doomed Group A on to a slow death through 1986.

All was however not lost – come back soon to read how Group N grew to become perhaps South Africa’s most successful production race series through the following quarter-century…

Next week: Post Fuel Crisis SA Modified Saloon Car Racing

This series will continue weekly until complete.

The History of South African Saloon Car Racing will be published in more comprehensive form in a new book anon…

Issued on behalf of SA Saloon Racing History

| What | : | The History of South African Saloon Car Racing Part 7 |

| Where | : | South Africa |

| When | : | 1981-1986 |

| Community | : | South Africa National |

For further information please contact michele@lupini.co.za

Click on thumbnails to Download images

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View

View